Chinatown’s Hidden Poverty

How a Big Family Struggles To Survive in a Tiny Room

Even after living in the U.S. for almost a decade, Muyi Yu still bursts into tears when talking about the size of her home.

She and her husband, Jianhua, are raising their four children in a 100-square-foot single room occupancy (SRO) dwelling in San Francisco’s Chinatown. They have no kitchen of their own and no sink or toilet, just a single room to house six people.

“I don’t know how to explain to my kids,” Yu said in Chinese. “I could only [lie] to them that we will move into a bigger place soon.”

Like other hundreds of SRO families struggling in the city, the Yus are living with extremely limited space while their underage children—two teenage daughters, ages 16 and 15, plus two 8-year-old twin boys—are growing up.

For them, simple survival in this expensive city while struggling with poverty is filled with challenges, but the harsher question is whether they will ever find a way out of this one room and into a home of their own.

San Francisco dedicates vast resources to ensuring its residents are housed, but the Yu family and hundreds of others like them face immense difficulty even with a roof over their heads. Hemmed in by the slow grind of bureaucracy and limited English proficiency, they can easily be trapped for a decade or more in substandard living conditions.

Keep scrolling to continue reading...

‘I Am a Failure as a Mother’

Yu couldn’t hide her frustrations about the SRO room, where the space is barely enough to place her family’s necessities.

Two bunk beds are set up in the corner with piles of clothes on the upper bed. All six family members sleep on the other three mattresses. Sometimes, Yu said, one of the twin boys has to sleep on the floor.

A desk, a shelf, a fridge and several boxes occupy nearly every inch of what’s left, leaving only enough space for one person to stand. Even the unit’s front door can’t be opened fully because the space behind it is used for storage.

Video by Mike Kuba and Jesse Rogala

“I think I am a failure as a mother,” Yu said through tears. “How can I let my children live like this?”

She worries that the small space will have negative impacts on her children’s academics, and also as the twin boys grow up, they will “run out of” what little room they have.

Working as a part-time senior care services provider, Yu’s salary is the main source to pay for the $700 rent every month. Her husband works infrequently, and most days, the couple serves as full-time caregivers for their children.

"My heart feels like it is being torn apart," Yu said. "We really need a larger space for them to study."

The Yu family of six includes four children. Anna (top), Weiming (bottom left), Weilin (bottom center) and Weiqiang (bottom right) often do homework on their shared bunk beds. | Courtesy Yu family

The Yu family includes four children. Anna (top), Weiming (bottom left), Weilin (bottom center) and Weiqiang (bottom right) often do homework on their shared bunk beds. | Courtesy Yu family

But Jianhua Yu, the husband, is more positive with his smile and perseverance.

“We have to suck it up now,” he said, using a popular Cantonese phrase (“頂硬上,” or "ding ngaang shoeng"), which means “bear the hardship and fight.”

Accepting the Unacceptable

As San Francisco spends billions of dollars every year to solve its housing crisis, residents SROs are caught in a squeeze. No matter how tiny or overcrowded a unit may be, its occupants are considered housed.

“Some SRO families are with multiple children,” said Yu. “Our situations are so difficult.”

In Chinatown, the only place where low-income and monolingual Chinese immigrants can reliably find housing for their families, the unacceptable SRO situation becomes a viable alternative to having no home at all.

SRO Families United Collaborative, a coalition group organizing local SRO residents, has located 432 families across the city, and the majority of them are based in Chinatown. But the actual number of SRO families living in the city is believed to be far higher, perhaps as many as 1,000.

Federal, state and city laws all prohibit residential overcrowding. According to San Francisco’s building code, every room with two people living in it should have at least 70 square feet, and any additional individuals living together should require 50 more square feet for each.

Children under age 6 do not count, though. For Yu’s family, the legal minimum room size for such a family should be 270 square feet.

However, enforcement is typically rare, according to a source from the SRO community who requested to be anonymous. There is a fear it may lead to unintended displacement or eviction, and the families may end up being on the street.

Six-year-old Annie Xu (center left) picks up new shoes at the Chinatown Community Development Center in San Francisco with her grandmother on July 28, 2010. The organizer, My New Red Shoes, provides homeless and low-income families with new shoes for school. | Liz Hafalia/SF Chronicle via Getty Images

Six-year-old Annie Xu (center left) picks up new shoes at the Chinatown Community Development Center on July 28, 2010. The organizer, My New Red Shoes, provides homeless and low-income families with new shoes for school. | Liz Hafalia/SF Chronicle via Getty Images

The Yu family’s landlord, the Chinese General Peace Association, is an umbrella organization of a dozen Chinatown groups run by several prominent Chinatown elder leaders. The association told The Standard that it is aware of the Yus’ situation, and was trying to help them by not raising the rent for years and connecting them to job opportunities.

The Ways Out?

Multiple assistance programs are available for SRO families. Notably, there are federal vouchers, local rental subsidies and pathways to apply for affordable housing units.

But the Yus have been waiting for years.

Juan Garcia, a senior community organizing supervisor from the Chinatown Community Development Center (CCDC), said the Yu family had been referred to the Section 8 housing voucher program years ago. From a public-assistance perspective, this represents their best option, but they have yet to see a response.

“Unfortunately, it has been taking longer than what we expected,” Garcia said.

He described the Yus’ case as a priority, because of the family’s size relative to that of their room. Many SROs are relatively larger, with a private kitchen or even two rooms.

Once a federal voucher is issued, the recipients need to find a new place and pay 30% of their income to rent it. The Section 8 voucher will cover the rest.

Garcia said CCDC’s goal is to move about 50 families out of SROs this fiscal year, and as many as another 30 or 40 next year.

“We don't believe SROs should be a place for families to live in,” Garcia said. “Definitely not to have kids grow up in SRO.”

Weiqiang Yu (left) and Weilin Yu (right) play games on a tablet on Feb. 1, 2023. | Benjamin Fanjoy for The Standard

The Yu twins play games on a tablet on Feb. 1, 2023. | Benjamin Fanjoy for The Standard

The San Francisco Housing Authority (SFHA), which oversees federal voucher programs in the city, declined to comment on specific cases but said it is expecting to issue vouchers in the future weeks for those experiencing long delays.

Along with other families, the Yus have faced long waits, because SFHA had been in crisis since it ran a $30 million deficit in 2018. The agency was banned from issuing vouchers until late 2021. New leadership has taken over since, and the city has paid to help cover the shortfall.

Garcia and his team have been helping local SRO families sort out the vouchers as well local rental subsidy programs, too. Normally, if a family is waiting to become eligible for Section 8 housing, they are not allowed to apply for local financial assistance, which typically functions as a kind of Plan B.

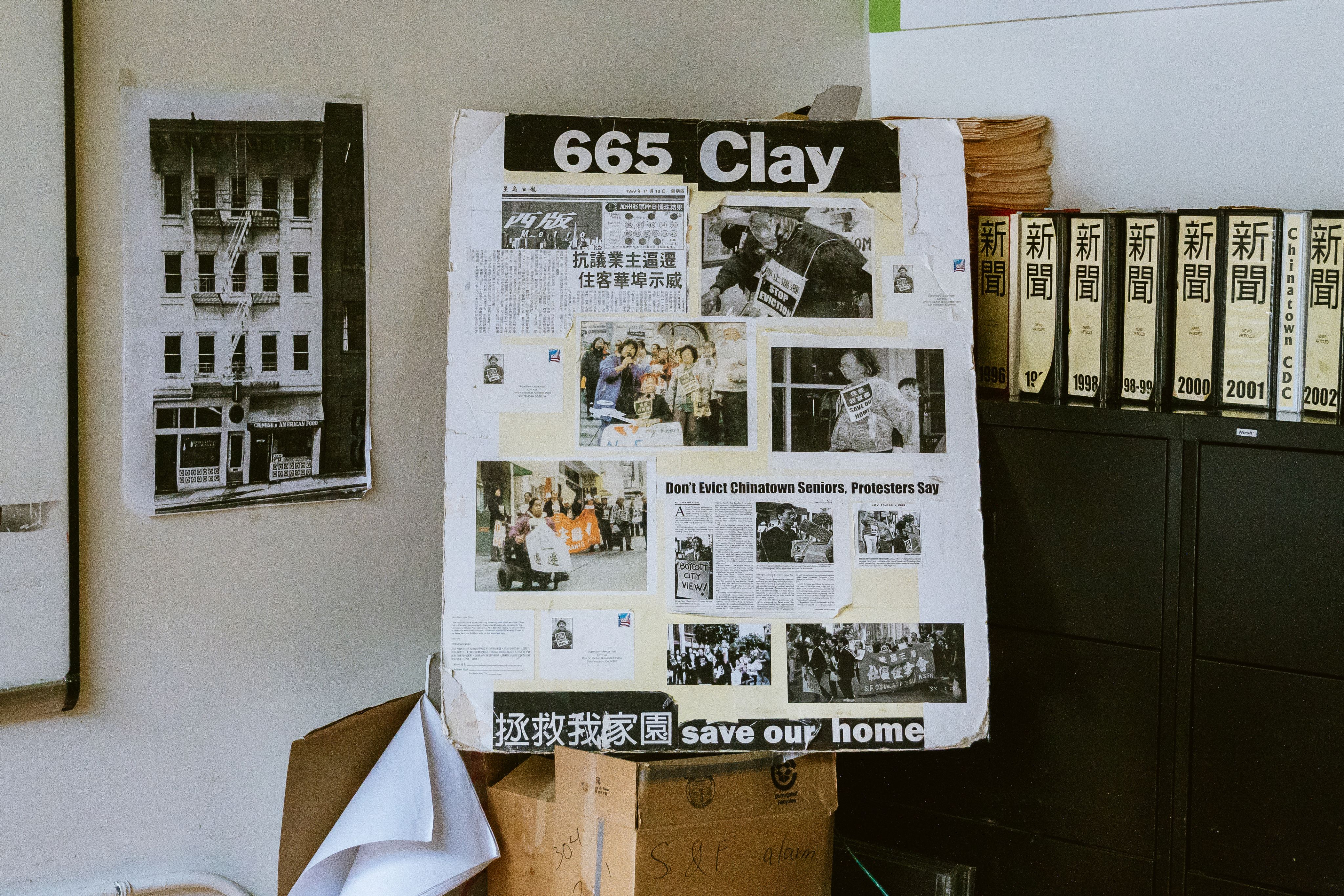

A collage of newspaper clippings and press releases about demonstrations and activism related to the potential eviction of residents of an SRO at 665 Clay St. is displayed at the Chinatown Chinatown Community Development Center. | Felix Uribe Jr. for The Standard

A collage of newspaper clippings about demonstrations related to the potential eviction of residents of an SRO is displayed at the Chinatown Chinatown Community Development Center. | Felix Uribe Jr. for The Standard

The Mayor's Office of Housing and Community Development (MOHCD), which oversees the local program, told The Standard that it has partnered with CCDC and the SRO Families United Collaborative to provide targeted rental subsidies for SRO families.

Under the partnership, “SRO residents may also receive high-quality and intensive services, including case management, housing navigation support, housing counseling, help interfacing with landlords, and other direct services,” MOHCD said in a statement.

Lanterns and window lights fill Spofford Street in Chinatown during the early morning in San Francisco on Feb. 10, 2023. | Benjamin Fanjoy for The Standard

Lanterns and window lights fill Spofford Street in Chinatown on Feb. 10, 2023. | Benjamin Fanjoy for The Standard

According to CCDC, the current budget for the rental assistance program is $1,576,596, spanning March 2022 to June 2023. About 25 SRO families have benefited from the program and moved to new homes.

SRO families can also apply for affordable housing through the MOHCD, but they don’t have much of an advantage over the general public.

MOHCD said that it manages six lottery preference programs, which provide priority for specific housing projects or affordable housing to qualified households.

Among them, local SRO families would only be qualified for the category of “Live or Work in San Francisco,” unless they are facing eviction.

Pedestrians walk below a mural in Chinatown on Dec. 13, 2022. | Benjamin Fanjoy/The Standard

Pedestrians walk below a mural in Chinatown on Dec. 13, 2022. | Benjamin Fanjoy/The Standard

Affordability is also questionable for SRO families if they choose to leave Chinatown, where long tenancies mean rents are often much cheaper. Citywide, San Francisco’s affordable housing prices are based on the overall median and average income levels, which can be out of many Chinese American families’ price range.

The collaborative has surveyed 320 SRO families and the result shows that their average monthly income is about $926 after the pandemic hit.

Barber Jun Yu plays an erhu for Supervisor Aaron Peskin during a campaign stop on Ross Alley. | Paul Chinn/SF Chronicle via Getty Images

Barber Jun Yu plays an erhu for Supervisor Aaron Peskin during a campaign stop on Ross Alley. | Paul Chinn/SF Chronicle via Getty Images

Supervisor Aaron Peskin, the president of the Board of Supervisors, represents Chinatown. He pointed out that without financial subsidies, SRO families cannot afford the vast majority of San Francisco's affordable housing.

“It will require a sustained funding commitment from the city and the state to keep the rents low,” said Peskin.

Struggling With Space

Navigating through the pandemic is no easy task for an SRO family, because if someone in the family gets sick, there’s no extra room for them to quarantine.

Last year, both Yu and her elder daughter caught Covid, so the stairwell in their building became a makeshift bedroom.

“I sat right here at night, and my daughter sat down there,” Yu said, pointing to different parts of the stairs. “We slept here for a week to avoid giving the virus to others in the family.”

And what’s worse than physically sleeping on stairs? Yu and her daughter had to get up earlier than everyone else in the building, because dozens of other tenants would complain that a person sick with Covid shouldn’t be staying in the building at all.

Interior details of the shared kitchen and bathroom that the Yus have access to from their SRO on Jan. 17, 2023. | Camille Cohen/The Standard

Interior details of the shared kitchen and bathroom that the Yus have access to from their SRO on Jan. 17, 2023. | Camille Cohen/The Standard

The Yu children do more than just sleep on the stairs. During the pandemic, as the schools required online learning, there was no way for four children to study in the same room at the same time. So both daughters would use the hall for class, too.

The two Yu daughters declined to be interviewed for this story.

The twins, Weiling and Weiqiang, may not be fully aware of their family’s situation. Born in San Francisco and having spent their whole life living in SRO, they may consider crowded spaces and a kitchen and bathroom shared with the whole building a normal thing for everyone.

Muyi Yu calls her sons into their apartment building on Feb. 1, 2023. | Benjamin Fanjoy for The Standard

Muyi Yu calls her sons into their apartment building on Feb. 1, 2023. | Benjamin Fanjoy for The Standard

Weiqiang Yu (right) and his brother Weilin Yu (left) play at the Willie “Woo Woo” Wong Playground. | Benjamin Fanjoy for The Standard

Weiqiang Yu (right) and his brother Weilin Yu (left) play at the Willie “Woo Woo” Wong Playground. | Benjamin Fanjoy for The Standard

Yu said that sometimes, when the building’s communal toilets are occupied for too long, the boys have no choice but to relieve themselves in the room.

On a warm January afternoon, the twin boys were playing and exercising in the Chinatown Willie “Woo Woo” Wong Playground, one of the few open spaces for Chinatown SRO families for outdoor recreation.

It’s not a big park, taking up barely half a city block—but if you’re a small child accustomed to life in a single room, it might feel as vast as the universe itself. The Yus tried to talk to their sons as they played, but failed to catch the boys as they ran around freely, enjoying the seemingly unlimited space.

Visuals for this story were produced by Sophie Bearman, RJ Mickelson, Mike Kuba, Jesse Rogala, Lu Chen, Camille Cohen, Benjamin Fanjoy and Felix Uribe Jr. This story was edited by Peter-Astrid Kane.