If Downtown SF Is Dead, Why Is Traffic So Bad?

With rush hour slowing to “mascara application” speed on Bay Area highways, drivers have one simple question: If Downtown San Francisco is dead, why is traffic so bad?

There’s no doubt San Francisco is having one of the worst pandemic recoveries of any major U.S. city—even the mayor thinks Downtown SF may never be the same. So with 150,000 fewer workers Downtown, it would be reasonable to assume a drive to the city wouldn’t encounter as much traffic as it used to.

That assumption would be wrong.

A closer look at the latest data shows bridge and highway traffic nearing pre-pandemic levels while public transit usage and commuter bus service remains a fraction of normal.

Translation: Commuters have returned to their cars.

Bustling Bridges and Highways

Though bridge traffic dropped to ghost-town levels immediately following the March 2020 shelter-in-place order, Golden Gate and Bay Bridge crossings bounced back within a few months and have been running at 85%-94% of pre-pandemic levels for the last year.

Early 2021’s hopes of a return to “normal” never really materialized in terms of commuters returning to Downtown on a regular basis. Yet many workers are still commuting to their San Francisco offices at least a few days a week—and the data show that many of them are likely driving.

“While a lot of folks are driving to work—no question—they may not necessarily be driving to the Financial District or SoMa,” said John Goodwin, the assistant director of communications for the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, who is seeing changes in SF traffic patterns.

Traffic coming off of I-80 onto Fremont St. in San Francisco, Calif., on Feb. 27, 2023. | Michaela Vatcheva for The Standard

Traffic coming off of I-80 onto Fremont St. in San Francisco, Calif., on Feb. 27, 2023. | Michaela Vatcheva for The Standard

“Maybe they’re meeting a friend for lunch who used to be in the next cubicle, walking their dog at Ocean Beach—or bypassing the city on the way to the Peninsula or SFO.”

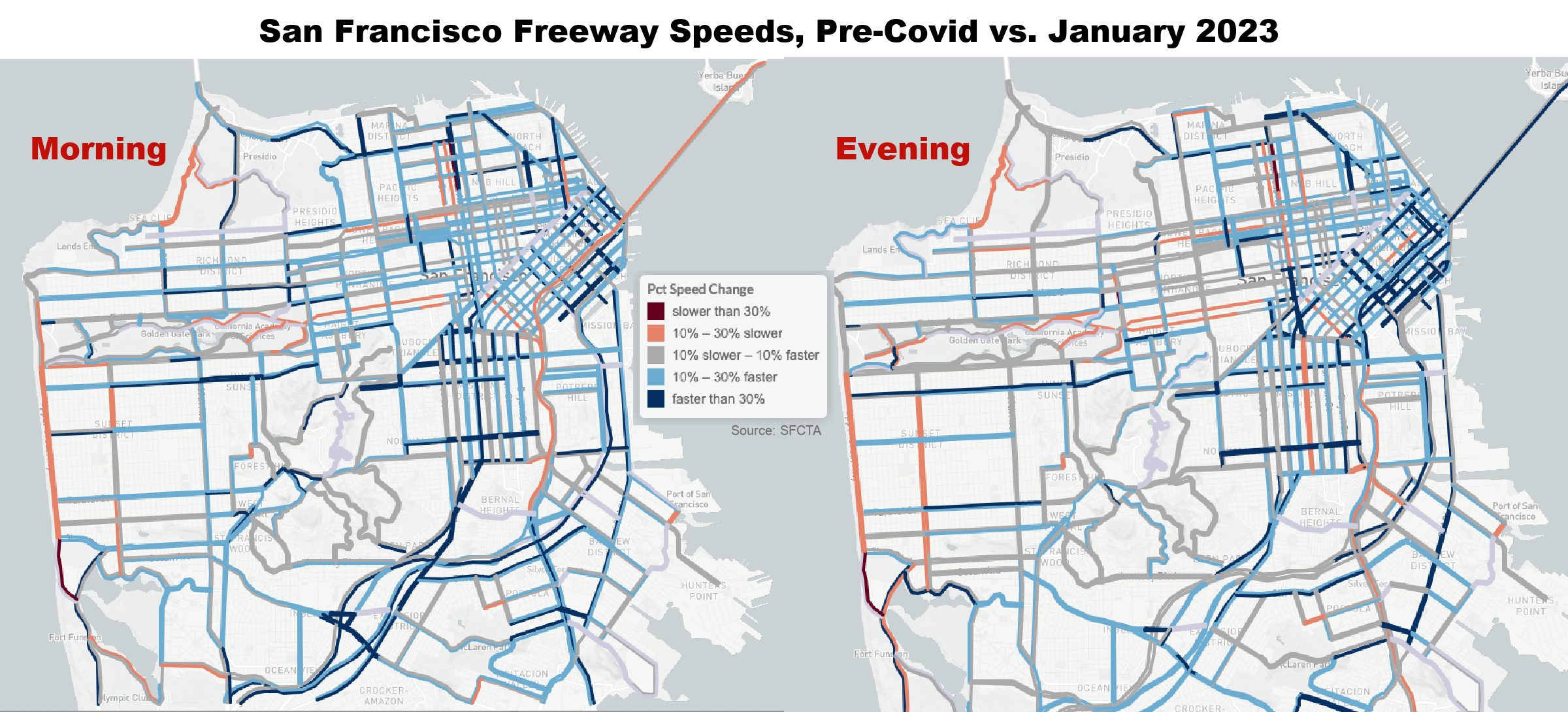

But trips around the city are taking longer than they used to. The SF County Transportation Authority (SFCTA) shows speeds on the Bay Bridge approach to SF and other surface streets have slowed to speeds even lower than those seen before the pandemic.

“Prior to the pandemic, congestion in the Bay Area had become overwhelmingly an afternoon phenomenon,” said Goodwin, whose responsibility includes the Bay Area Toll Authority.

Though the afternoon crush to get on the Bay Bridge eastbound used to last from as early as 1 p.m. to as late as 8 p.m., now it is much shorter, from, say, 3 p.m. to 6 p.m.

“Maybe traffic is just as intense at the absolute peak, but the peak isn’t as long as it used to be,” Goodwin said.

Morning commuters from the East Bay aren’t as lucky. SFCTA data show vehicle speeds during morning rush hour—heading westbound from Treasure Island to the Fremont Street exit—are 22% slower than they were before the pandemic. Conversely, afternoon rush hour speeds are reaching levels 34% faster than in early 2020.

BART Ridership Stalled

SF leaders have been watching public transportation figures closely as an indicator of the city’s pandemic recovery. Analysis from the Controller’s Office shows BART ridership rebounded from Covid lows of 2020 but the number of passengers exiting at downtown SF stations is only 30% of what it used to be.

Whether pre-pandemic riders are simply not coming to their SF offices anymore or whether they are bothered by service delays or unhoused riders, BART’s portion of “very satisfied” riders dropped from 39% in 2020 to 26% today.

“When public transport is no longer frequent and easy accessible, people will revert to nonshared rides because they still need to get where they need to go,” said John Ford, executive director of Commute.org, the transportation demand management agency of San Mateo County. “Commuters often fall back into driving their own car, and that’s not what our air quality needs.”

Empty Express Bus Seats

Another challenge for commuters is the drop in the number of commuter express buses destined for Downtown SF—even from the avenues and other distant parts of the city itself.

AC Transit’s express routes to the Salesforce Transit Center were always a favorite with East Bay commuters. Trouble is, the number of routes and riders on those buses has not recovered to anywhere near pre-pandemic levels.

“We certainly have people riding the transbay lines and East Bay riders enjoy riding AC Transit, there’s no question about that,” said Robert Lyles, head of media affairs at AC Transit. “We still have reliable, effective service into San Francisco, but the ridership is just not there compared to pre-pandemic.”

Before Covid, AC Transit ran 24 routes making 289 westbound trips and transporting nearly 17,000 people into SF every day. Today, 15 of those routes have been restored, but the most recent data for September 2022 shows fewer than 4,000 people got on board daily.

Looking north from the Golden Gate Bridge Overlook towards Marin County, Calif. | Getty Images

Looking north from the Golden Gate Bridge Overlook towards Marin County, Calif. | Getty Images

In Marin, Golden Gate Transit now offers just 55% of the service it had before the pandemic. Currently, its commuter routes have only 17% of the bus riders and 32% of the ferry riders they had in 2019.

Commuters in Mill Valley successfully rallied to get one commuter route reestablished after the pandemic, but a spokesman said customer demand for SF service has not materialized in other parts of the county.

And without express buses, many Marin commuters have no choice but to jump in their cars.

Missing Peninsula Commuters

In the South Bay, SamTrans does not offer many commuter buses direct to San Francisco, but it manages Caltrain service. In 2019, the trains carried 63,000 riders per day. Last October, that figure was only 18,583.

Another factor influencing traffic on the Peninsula is usage of last-mile shuttles that connect South Bay commuters to transport hubs.

“We exist to make sure people have options to driving alone,” said Ford of Commute.org, which specializes in running shuttles from transport hubs into the neighborhoods of San Mateo County. “We’re agnostic about whether they get on a ferry or bus or train or BART, we just get commuters that last mile home.”

Commute.org still makes the same number of shuttle trips, but only has 40% of the riders it had before Covid. It’s a financial challenge faced by many transit agencies that have tried to retain the same level of service amid declining revenue from riders.

“It’s really tricky. How long can you continue to run with ridership far below capacity and yet still provide needs for the ‘transit-dependent’?” says Ford. “What’s going to happen? Will all these agencies continue to provide that level of service or have to cut back for cost reasons?”

AC Transit plans to attack the issue head-on this month. The agency will re-examine all its routes in a post-pandemic light and decide which ones need to be realigned based on public hearings where riders can weigh in.

“How do we realign our bus lines and services to meet the demands of post-pandemic riders?” Lyles said. “We want to see where our service is, where the riders are and how to rework our lines to be fiscally responsible.”

The visuals in this story were produced by Jesse Rogala, Paul Kuroda and Michaela Vatcheva.