Meet the Volunteers Saving Baby Bluebirds in the Bay Area

Regular golfers at the Santa Teresa Golf Club in San Jose recognized a man dressed in khaki trekking along the greens on a recent Saturday. He reached a long, hooked pole high into the treetops.

“Hey, Lee!” they called from their golf carts. “Checking on the bluebirds?”

The bluebirds weren’t nesting yet, but Lee Pauser was getting their future homes ready. One by one, he lifted birdhouses down from the branches and cleaned them out in preparation for a new nest and a clutch of baby birds.

The retired IBM programmer has been making and monitoring bird boxes for more than 20 years: As he explained, after raising his own children, he decided it was time to help the birds succeed in raising theirs.

In San Jose, at the golf course and a nearby county park, he takes care of about 50 nesting boxes every year, what he calls his “bluebird factory.” Some 16 native species make their homes in Pauser’s boxes, too: tree swallows, kestrels, barn owls and many more cavity-dwelling birds.

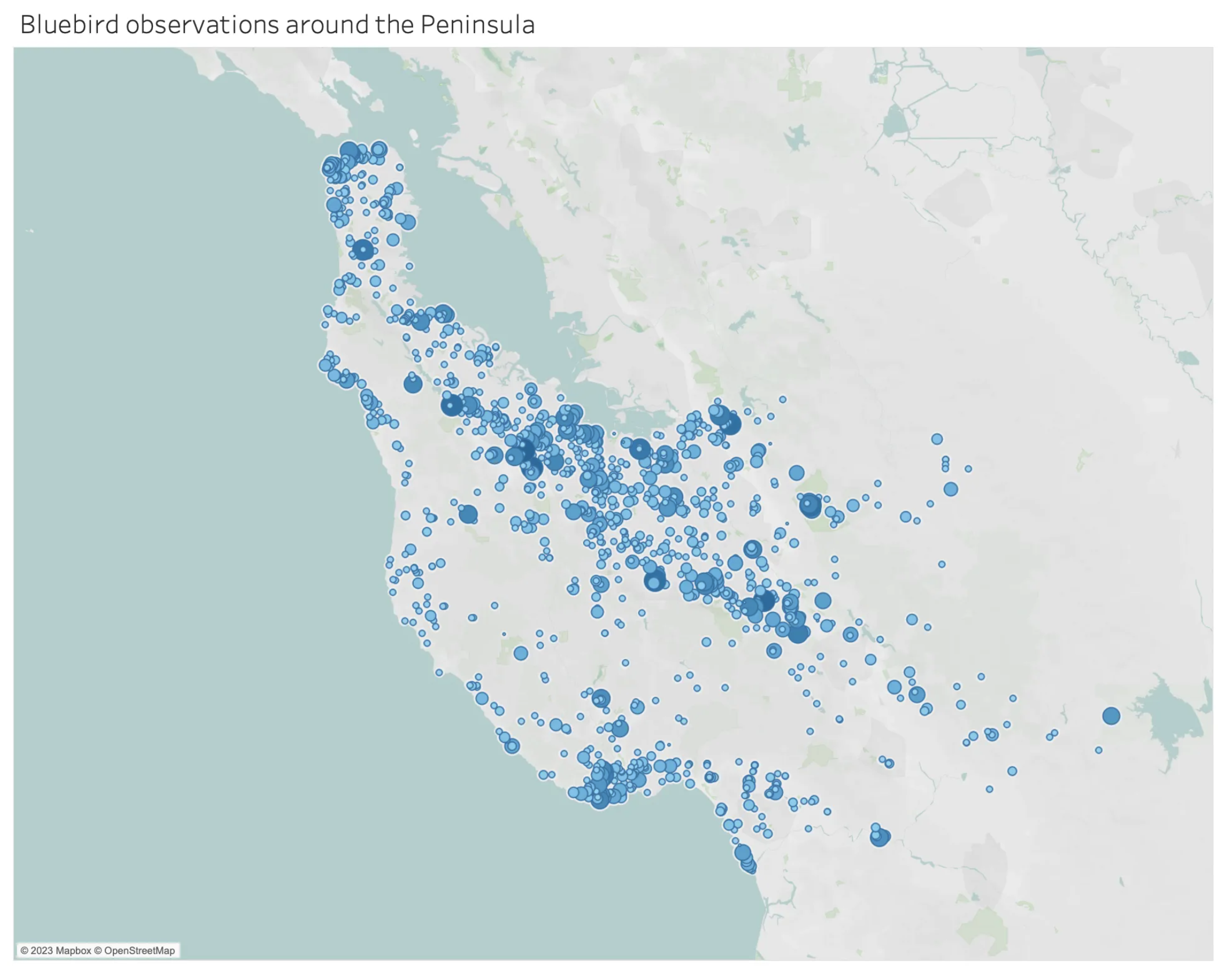

Birders around the Peninsula recorded more than 25,000 western bluebird sightings in 2022. Click here to explore an interactive map. Source: eBird data. | Chart by Grace Doerfler

Pauser’s nest boxes have been remarkably successful in helping these kinds of birds flourish in the Bay Area. By his own count, he’s helped 18,271 birds fledge, including more than 7,000 western bluebirds. Last year alone, Pauser saw more than 500 baby bluebirds leave the nest. He submits all his nest box data to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, giving scientists a glimpse of bird life on the Peninsula.

The boxes are Pauser’s own design, with every luxury a bird could want: gutters to keep rain away from the nest, air vents to maintain healthy temperatures, specially designed entryways too deep for predators to reach hatchlings.

Cavity dwellers once nested mostly in dying trees, often in holes drilled by woodpeckers. But that natural real estate is scarce these days. Humans have taken away many of these birds’ nesting spots by clearing away deadwood from forests. Now, birds increasingly rely on human-made boxes to raise their young.

Extreme weather is one of the most serious threats to the birds’ survival. Dino Sakkas, a South Bay-based nest box monitor, said the drought of recent years in California made it harder for baby bluebirds to survive. This year’s heavy rains, though, might bring more insects, making it easier for the birds to get the food they need. But a lot of factors affect birds’ survival every spring, and Pauser said the volatility of climate change is increasingly a challenge for birds.

Around the world, bird populations are in severe decline due to habitat loss, pollution, climate change and other issues. BirdLife International’s State of the World’s Birds 2022 report showed nearly half of the world’s bird species are decreasing. The United States ranked eighth globally for the greatest number of threatened species.

In the U.S., bluebird populations dropped precipitously from the 1920s to the 1970s, sparking conservation efforts that spread from the East Coast and reached California in the early 1990s. These efforts have had significant success in restoring the birds’ numbers.

While it’s difficult to get an accurate snapshot of the number of bluebirds in the Bay Area, data indicates the birds are flourishing, due at least in part to the efforts of bird box monitors. Last year, birders in the area recorded over 25,000 western bluebird sightings on eBird, a popular birdwatching app—a significant increase from just a few years ago, although it’s hard to tell if that’s due to more birds, more birders or both.

Lee Pauser examines a nest box in San Jose in preparation for nesting season.

A curious western bluebird inspects one of Pauser's nest boxes.

Explore the Exteriors and Interiors of the Nest in 360 Degrees

Explore the inside of the nest box in 360 degrees. The nest includes a ladder by the entrance to help birds like swallows exit the box more easily—the red light you may see on the eggs is from the camera. | Video by Phoebe Quinton and Zack Boyd

Habitat is uniquely important for these bird species, said Tyler McFadden, an ecologist at Oregon State University.

“Cavity nesters are a really interesting subset of birds,” McFadden said. “Their whole life history and life strategy is so closely tied to a very specific structure, and that's the presence of standing dead trees that they can make a cavity and nest in.”

McFadden, who earned a doctoral degree in evolutionary biology from Stanford, has worked on long-term studies of Bay Area bird populations, giving him insight into the factors that affect western bluebirds and other cavity nesters.

Explore the outside of the bluebird nests in 360 degrees. Reporter Grace Doerfler stands under the 360 camera in the second scene, and reporter Tyler McFadden can be heard in the background. | Video by Phoebe Quinton and Zack Boyd

“If you see a tree that's dying, [urban foresters] try to remove it early on because it presents a very real risk to human health,” he said. “When we're thinking about mitigating wildfire risk and reducing the amount of fuels out on the landscape, deadwood is often one of the first things that gets targeted.”

Most people might assume that deadwood in a forest is bad or unhealthy, but it’s actually essential to the ecosystem’s health, McFadden said.

“Around half of all forest species are associated with deadwood at some point during their lifecycle,” he said. “So if you don't have the deadwood, it's a dead forest.”

Bluebird monitoring offers insight into the health of the bird population overall, bird box monitors say. Because the bright blue birds are so recognizable, it’s easy to notice when they’re absent. When bluebirds are abundant, it’s often a good indication that other cavity-dwelling birds are doing well, too.

Trees pockmarked with holes are prime real estate for cavity-dwelling birds.

Woodpeckers—like this acorn woodpecker pictured here—usually create the cavities where bluebirds take up residence.

Human-made nest boxes mimic the natural cavities where some birds feel most at home.

The California Bluebird Recovery Program and the Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society are two organizations intervening to help birds locally.

Mike Azevedo, who coordinates the nest box program for volunteers in Santa Clara County, said the local Audubon SocietyS has been running the program since 1997. While it took a couple of years for the birds to catch on, they’re now easy to spot around the region—a testament to the boxes’ effectiveness.

“The program has been a success, but we can’t drop the ball,” he said.

Azevedo hosted training sessions this spring for new nest box monitors. When volunteers get involved with the program, some fall in love with the birds and help care for the boxes one season after another.

Western bluebirds enjoy the sunshine in San Jose, Calif. on Feb. 18, 2023. | Phoebe Quinton

Western bluebirds enjoy the sunshine in San Jose, Calif. on Feb. 18, 2023. | Phoebe Quinton

Sakkas, who’s one such volunteer, has always loved bluebirds. The Cupertino resident said when he sees them, he feels sure he’s going to have good luck. But in the past couple of years, since retiring from Lockheed Martin, he’s taken a more active role in helping the species thrive.

For Sakkas, who is beginning his third year of bluebird nest box monitoring this spring, caring for the nests is a way to tend to the Earth and give back now that he’s retired. He and a friend care for 16 nest boxes in Fremont Older Open Space Preserve near Cupertino. They check on the boxes every week from midwinter until the baby birds take flight in early summer.

Sakkas said he had loved birds since he was young. He has long kept bird feeders in his backyard to watch local species.

“It’s great,” he said. “It’s like bird TV, I call it.”

He first noticed bird boxes on a visit to McClellan Ranch, a nature preserve in Cupertino that’s home to the local chapter of the Audubon Society. The boxes piqued his curiosity, and he asked the Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society how he could help.

Now, Sakkas is something of an expert. He knows how to look at the grass and twigs in a box to tell what kind of bird is building a nest, how to calculate when a clutch of eggs will hatch and how to check on a box without disturbing the eggs. The nest boxes on his trail attract chestnut-backed chickadees, ash-throated flycatchers and oak titmice, as well as western bluebirds. Throughout the nesting season, he records all his observations and sends them to the California Bluebird Recovery Program’s database.

"You’re getting data to understand how this really important species is faring in this world,” he said.

Dedicated individuals like Sakkas and Pauser are one big source of the California Bluebird Recovery Program’s success. After two decades of monitoring nest boxes and watching more than 18,000 baby birds successfully fledge, Pauser has myriad stories to tell. Some of them are tragic, like the stories of mothers and their nestlings killed by predatory sparrows. Some are sweet, like the first time that Pauser watched bluebirds fledge from a nest box he was monitoring. And all are imbued with the care he invests in the birds and the pride he takes in his conservation work.

“It gives me satisfaction,” he said, “because I’m doing some good.”

Asked whether the birds recognize him from his regular presence around their nests, he paused reflectively.

“I think they do,” he said. “I think they recognize that I’m trying to help.”

Baby bluebirds respond to Dino Sakkas's whistle. | Courtesy of Dino Sakkas

Throughout the nesting season, nest box monitors are on alert for all kinds of threats to the baby birds and their parents. Extreme heat and cold, predatory birds, drought, hornets and maggots can all pose a threat to hatchlings' survival. Pauser said that in most of his nests, he sees broods of five or six eggs on average. About 90% of the eggs that he monitors hatch, and just over three-quarters of those hatchlings successfully fledge, the baby birds overcoming a host of challenges.

“I'm keenly aware of the difficulties they encounter and rejoice quietly when the nestlings fledge,” Pauser said.

Sakkas remains hopeful that this year will be a good one for bluebird families. Regardless, like other local bird box monitors, he’ll be hiking along his trail in the Fremont Older preserve, doing his part to help the birds survive.

“I want to leave the Earth a little bit better, leave the environment a little bit better, than when I was born, if I can,” he said.

ABOUT THE STORY

The video inside a bird box uses a model box containing an old bluebird nest with unfertilized eggs. No nesting birds were disturbed in filming.

The 360-degree videos were filmed by Phoebe Quinton and Zack Boyd using Insta360 cameras.

The 360-degree drone videography was filmed by Grace Doerfler using an Insta360 Sphere camera on a drone.

Data analysis was completed by Grace Doerfler using data on western bluebirds from eBird and data on nest box monitoring from Lee Pauser. Data visualizations were created in Flourish and Tableau.